Postmemory, Psychoanalysis and Holocaust Ghosts

- Rony Alfandary

- Dec 22, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: May 21, 2022

Postmemory, Psychoanalysis and Holocaust Ghosts, published on July 2021 by Routledge.

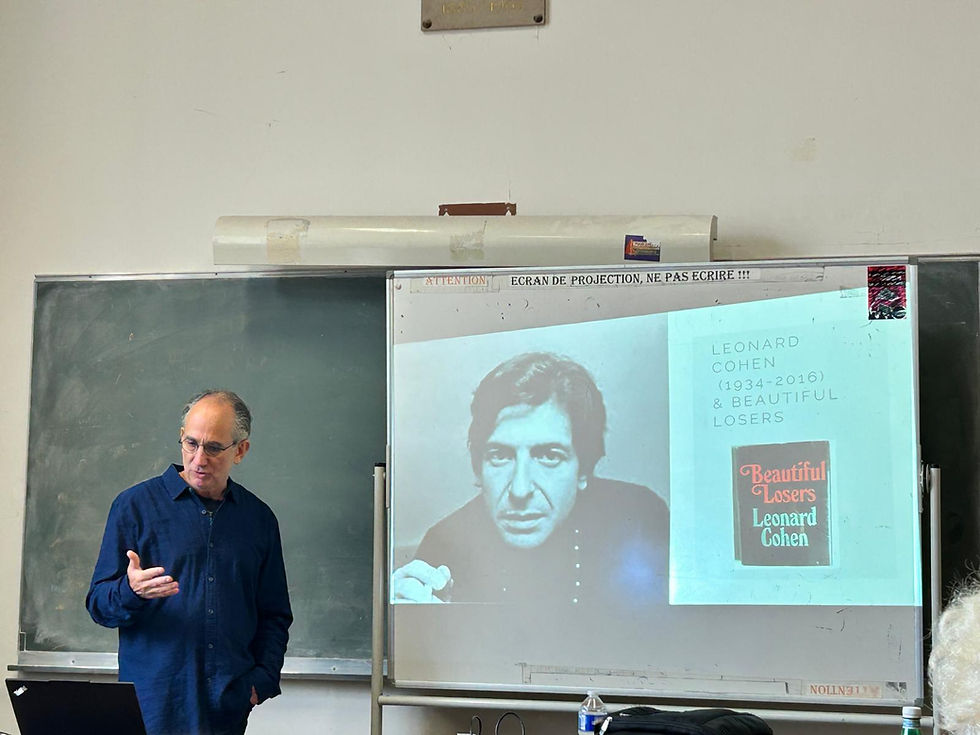

I have been writing and lecturing about the Cohen collection for some time. I first presented the raw material in a conference in Salonica in November 2014 "The Holocaust and its Aftermath".A short video shows highlights of e conference. In March 2015, a second lecture was given as part of the "Migration, Exile and Polyphonic" conference in Barcelona. Later that year, I gave a talk in Hebrew as part of a Ladino conference at Bar-Ilan University in Israel. In March 2017, I gave a lecture at "The Holocaust and its Aftermath from the Family Perspective" in Prague.

A Review of the book by Ross Bradshaw was published in Jewthink May 2022

A review of the book by Dr. Dominic Green appeared in the September edition 2021 of the New Criterion.

A review in Haaretz September 10th, 2021

An earlier version was published in Alaxon, 2018

The book is a testimonial study inspired by the letters and documents found on four separate occasions and locations. They were written in four different languages: most of them are in French, some in Ladino, a few were written in Solitreo [i] and a few legal documents are in Greek. The choice of these languages, including the dominance of some, is indicative of the national and cultural complexity that the Cohen family enjoyed in Salonica, not unlike other Jewish families at that time.

How does a person respond to the fact that the formative event of their lives occurred long before they were born? Especially when that event was the Holocaust? In his immensely readable microhistory of the Cohen family from Salonica and Paris, Rony Alfandary skillfully weaves a narrative that grapples with these questions, telling the tales of testimony bearers, human memorial candles of the second and future generations of a family of Holocaust survivors. Listening to voices painfully and suddenly silenced long ago, he uses a treasure-trove of documents to describe and analyze the evolution of ‘postmemory’, showing how it has affected the performative and memorial psyche of survivors’ families, continuing on to future generations.

Judy Tydor Baumel-Schwartz, Director, Finkler Institute of Holocaust Research, Bar-Ilan University, Israel

Rony Alfandary’s evocation of his family’s impending fate in 1930s Salonica and Paris is profoundly affective. This collection of letters and photographs is powered by his acute sense of his own postmemory and his professional insight into trauma. It stands beside the work of Eva Hoffman and Sophia Richman as testimony to the perennial sense of Jewish life as (in the words of one surviving relation) ‘intelligent, loved but unsafe’. Alfandary juxtaposes the candid humanity of his family’s self-expression with an awareness of difference and ‘the mystery of Otherness.

Richard Pine, Durrell Library of Corfu

In this original and interdisciplinary family history, Rony Alfandary, a clinical social worker, writer and photographer, creates a memorial for the members of his family that perished in the Holocaust. This book takes the reader from Salonica to Paris to Tel-Aviv and back again, on a journey that explores the profound role of postmemory in the lives of those born in the aftermath of the Holocaust. Alfandary is both a storyteller and a therapist, guiding the reader beyond mourning, into a space that allows for creativity and perhaps even joy.

Laura Hobson Faure, Professor of Modern History and Chair of the History of Modern Jewish Societies at the Université Panthéon-Sorbonne-Paris 1

Through the collection of letters sent by members of a Jewish family between 1925 and 1942, this fascinating book explores phenomenological and psychoanalytical aspects of the Holocaust and its associated trauma, and the impact on future generations of the same family.

This book charts a postmemorial study of the Cohen family of Salonica which branched out to Paris and Tel-Aviv during the 1920s and 1930s. The exploration of the contents of four boxes containing hundreds of letters, pictures and other documents portray a microhistory of one family that was once a part of a thriving community. Showing how the shadows of trauma can be passed through the generations, the book uncovers the tragedies that befell the Cohen family, and how the discovery of these materials has affected existing family members.

In an intriguing work of postmemory research and analysis, this book appeals to both scholars of the holocaust and psychoanalysts interested in the unconscious impact of history.

The first box was the one left behind by Rita and Samuel in their apartment in Israel. It was kept in the wardrobe and was taken by Rita’s children after Samuel passed away in 1990. The opening of that box was the beginning of the journey that this tale is a part of. The letters in that box were the ones Rita and Samuel received from Rita’s mother, brothers and sister from Salonica and Paris between the years 1930 to 1941. That box contained about eighty letters, handwritten in French and Ladino, as well as their envelopes and some postcards and photographs.

The physical state of those letters is often quite poor as the box went through serious physical mishaps as it was subjected to at least two floods, while the family lived in a small neighbourhood called Sova, located in the Ayalon Wadi in south Tel-Aviv during the 1930s, soon after they arrived in Palestine from Salonica.[i] Quite a few of the letters cannot be read due to their poor condition. Some of them are smudged badly. Some are torn. When the box was first opened, some of the letters had to be treated very gently. They had to be dried and pressed, which was done lovingly and with much pain by Rita’s oldest daughter, Esther.

Amongst them was also found a note in Ladino written by Rita, the epitaph of the book.

(Souvenir de mis ermanos deportados a la Segunda Guerra al 1942. Quero yo, vouestra madre, y nona Parente, que vos acodrech siempre de eyos, que la familia Cohen non suembare a vouestro aouvenir. Vouestra madre y nona. “A souvenir from my siblings who were deported during WW2 in 1942. I am your mother and grandmother want you to remember me always and the Cohen family, so they are not lost from your memory. Your mother and Grandmother.” ) The box of letters was not opened immediately after Samuel’s death. The box remained unopened for a couple of years and was finally opened and examined when I asked about the addresses of the family in Salonica, as I was about to visit the city on my journey through Europe in 1993, a journey that began in Berlin and ended in Greece, while en route I visited, amongst other places, the Auschwitz death camp.

Once the box was opened, things began rolling fast. The Salonica addresses from which letters were sent during the war years were located and visited both by me and in following years by other members of the family. None of the original buildings survived. What was more significant was that the opening of the box ignited a dormant hope in Rita’s children that perhaps someone of the family had survived. They knew that their father had spent many efforts in trying to locate surviving family members during the 1940s and 1950s, as many other Jewish immigrants from Europe did in those years. It was not only Rita’s family that he was looking for but his own uncles, aunts and cousins who too stayed in Salonica and did not survive. He was unable to find a single soul but did the least he could - register their names with Yad Vashem in 1957. After he ceased searching, his siblings did not continue his efforts. But then in 1993, as they looked through the letters in the box, the addresses in Paris from which Leon sent his letters, captured their attention. Especially the last address, 5 Rue le Goff. Rita’s children began investigating. The beginning of the search was akin to looking for a needle in a haystack. But through hard work, much perseverance and some good luck, a lead was found. Benjamin’s wife, Elly, and Esther’s friend, Ines Cohen (no relation), came across a photograph of Leon and Bondy in a publication by Serge Klarsfeld. They were able to contact Serge and his wife, Beate, who provided them with the name of the person who gave them that photograph, Mireille Florent Saül from Paris. It took some very intensive overseas telephone conversations with the French telephone company, until Mireille was indeed found. In a very emotional telephone conversation, it was confirmed that she was the daughter of Leon Cohen’s wife’s sister, Rosette (Rosa) Saül, who lived in Provence. Even though the Saül family was only linked to the Cohens by marriage, it was the closest they got to finding a lost relative. At first, it appeared that Rosette was not too keen to share information regarding what Leon and her sister Bondy may have left behind in that flat.[ii]

Thanks to Mireille’s insistence, the second box of letters was soon “found” amongst Rosette’s possessions. The box had been kept, apparently in the flat in 5 Rue le Goff soon after the war and was there for two decades, while Rosa’s and Bondy’s brother, Edmond, lived in it. It was only after Edmond left the flat during the late 1950s that the box was given to Rosette and kept at her home in Provence.

That box of letters contained nearly 100 letters and postcards received by Leon Cohen, first as a single man and then as married man between 1931 and 1941. These were letters he received from his mother, his sister Ines, his brothers who stayed in Salonica, from his older brother Isaac, whom he followed to France, and from his sister, Rita, in Palestine. The flow of letters from this box stopped in 1941.

The third box of letters and documents was discovered, again “accidentally” in the same house in Provence in 2014 by Rosa, and contains about eighty letters, seventy postcards and about fifty photographs received by Leon Cohen from his mother and siblings in Salonica, Paris and Palestine between 1927 to 1940 and contains letters and documents Leon took with him to Paris after he left Salonica.

The discovery of the fourth box, early in 2017, was even a bigger surprise. It contained more about 100 letters, 100 photographs, 150 postcards as well as many other items such as Leon’s business stamps, diary, cheque book, various legal documents, visiting cards, two small paintings done by an unknown artist and other objects, covering the period between 1924 and 1931. It was apparently found in the same house in Provence but for some reason was only announced recently. All attempts by the author and others to understand how that was possible, were met with non-descript answers, ranging from ‘there was a big mess when we moved’ to a simple ‘I just don’t know. I just found it.’ It is most tempting to speculate about the real and deeper layers of such a denial, but as it was felt that this was a sensitive issue, perhaps covering a family secret, and risked causing unnecessary hurt, it had been dropped for the time being, leaving much to wonder about. What is the story behind the gradual revelation of the boxes? What secret narratives lie beyond?

And so today, the collection contains more than 400 letters, both family letters and business letters relating to Leon Cohen’s occupation as an accountant in France, more than 200 postcards showing mostly Leon and Bondy’s travels in France before the war and over 200 photographs, quite a few of recognizable family members but mainly of people whose identity remains unknown to date, as well as many other times.

Overall, the Cohen collection holds more than 800 items allowing more than a glimpse into the life of Leon Cohen and his family. There are many possible narratives that can be reconstructed from the collection: the personal exchange between Leon and his siblings and mother; the professional letters exchanged with his business associates; the pictorial narratives depicted through the postcards showing Leon and Isaac’s travels in France during the happy years preceding the war; the pictorial narrative told through the photographs kept in the collection, including the many photographs where unidentified people are documented; the narrative of the various artifacts found in the boxes. All these narratives will be touched upon in this book but in no way will be subjected to exhaustive analysis. That will have to be left for future research.

For samples of the full collection, follow the links below:

Newspaper Clips, letters, photographs, postcards, diary, visiting cards, business stamp, chequebook, pocketbook, and more....

Comments